German Prisoners of War

Fairfax County 1945

By: M.Callahan

October 2014

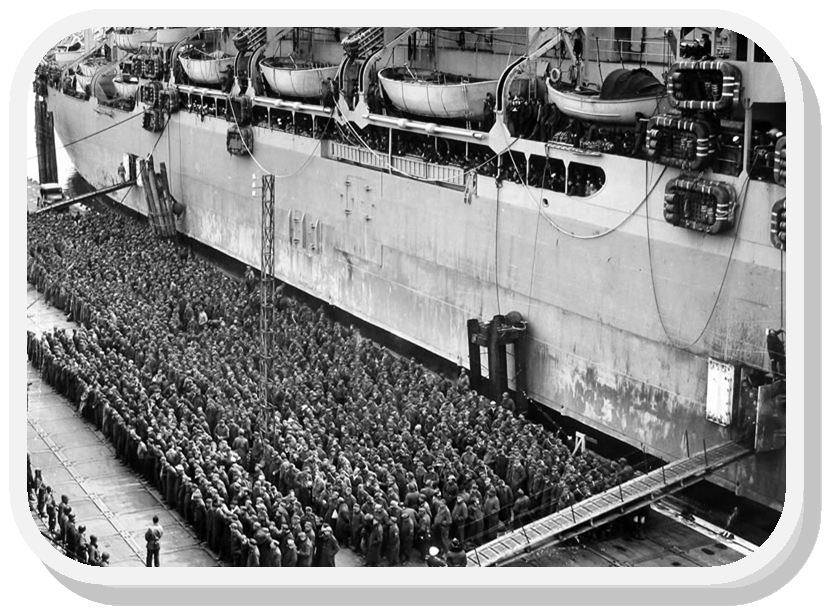

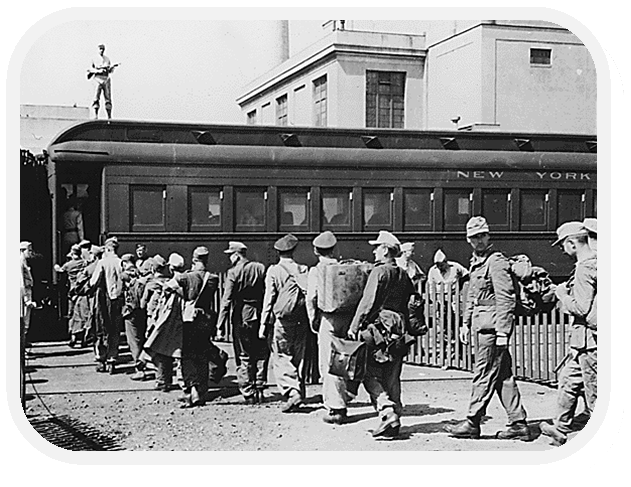

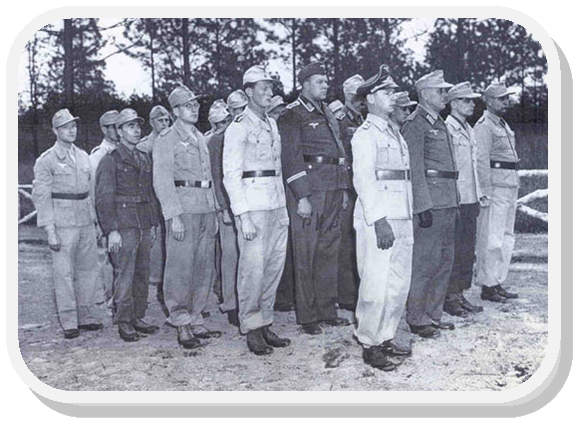

In May 1943, following the success of the North Africa campaign, over one hundred and thirty thousand (130,299) German Prisoners of War arrived in America. Sent by train to embarkation ports at Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers, these prisoners were given books by the Red Cross to pass the time. The length of their wait depended upon the availability of vessels, usually a returning Liberty ship. The trans Atlantic voyage lasted up to six week with ships landing at either Camp Shanks, NY or Norfolk, VA. Upon arrival, prisoners were spirited through a bureaucratic registration process, sorting to separate the die-hard Nazis. Immediately thereafter, prisoners traveled by train in comfortable Pullman cars, unlike the cattle cars used for German troop movements throughout most of Europe. (1)

As Allied forces successfully fought their way from North Africa through Italy, from Normandy to Berlin, unexpectedly large numbers of German troops were captured. The best containment for these prisoners was far from the theater of war; clear across the Atlantic certainly qualified. Britain was experiencing devastating food and housing shortages thanks to ships sunk by German wolf packs, and heavy Luftwaffe bombings; making the necessity to feed additional mouths an equation of diminishing return. Britain had managed to intern many prisoners, (primarily German and Italian) turning them into laborers, especially farm labor, which supplemented the dedicated services of the Women’s Land Army, formed to replace the male farm hands serving in the Armed Forces.

By mid-1942 America was only beginning to take prisoners, when the number of Axis prisoners held by the British had reached crisis proportions. The US quickly dealt with the issues of containing, housing, clothing, and feeding tens of thousands of prisoners. (2)

Although the majority of internment camps in the US were in the warmer climates of the south and south west, by the end of the war, 425,000 German prisoners lived in 700 camps in 46 states throughout the US.

Virginia interned POW’s in ten major camps, with up to seventeen smaller satellite camps under their direction, including one on Lee Highway in Fairfax. The highest reported POW population throughout Virginia reached 22,131. Camp Lee, three miles east of Petersburg, was in operation the longest at 27 months, and Fort Eustis in Warwick County held the most POW’s at 4,345. In Virginia, prisoners engaged in forestry, agriculture, or food processing work.

On January 2, 1944, the Empress of Scotland unloaded prisoners from North Africa. Reinhold Pabel ably describes the experiences shared by the overwhelming majority of POWs.

“And so we went ashore at Norfolk, Va., in the morning hours. After going through the customary delousing process we marched to the railroad station. There were immediate shouts of "Man, oh, man!" and "How about that?" when we followed orders to board the coaches of a waiting train. Most of us had always been transported in boxcars during the military service. These modern upholstered coaches were a pleasant surprise to everyone. And when the colored porter came through with coffee and sandwiches and politely offered them to us as though we were human beings, most of us forgot ... those anti American feelings that we had accumulated …

The guards at each end of the coaches had strict orders not to take chances with us. Whenever someone had to go to the washroom he was expected to raise his hand like a schoolboy in class so the guard could ... accompany him safely to the head of the car. . . . It all looked very amusing to me and I kept thinking what a beautiful confusion one could create by conspiring with a number of the boys in the coach to raise their hands simultaneously. What would the guards have done?

No matter how divided we prisoners might have been in our opinion of America, we were nearly all quite curious to find out ... what the United States would really be like … En route through Virginia and Kentucky we pressed our noses against the windowpanes to take in the sights. The first impression we had was the abundance of automobiles everywhere.” (3)

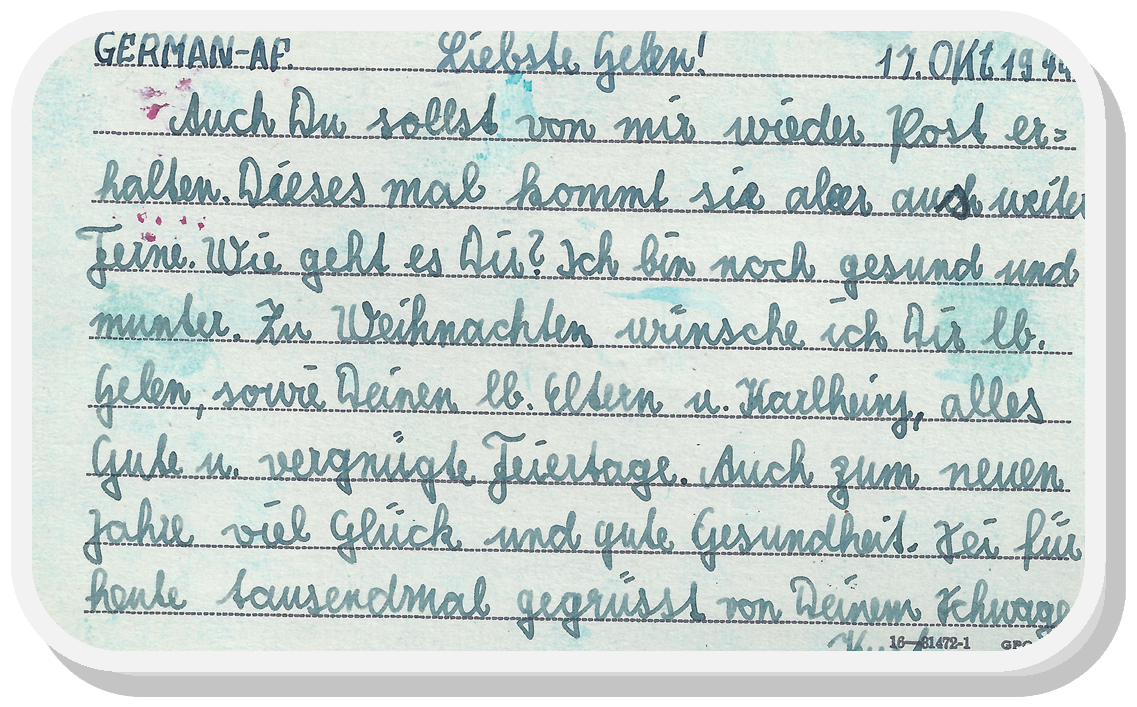

America’s policy was to treat prisoners humanely in order to receive reciprocal treatment for US prisoners. POW’s were encouraged to write their families and tell them how well they were being treated. (In time, word would also reach the German government/ranking military) Instinctively, the average German soldier knew he had won the lottery to be taken prisoner by the British or Americans rather than the Russians, whose reputation for harsh, often grossly inhumane treatment, had already reached the battle lines.

The US also permitted frequent, even surprise visits by the International Red Cross for impartial review of internment facilities, and the procedures followed in the US POW Program; honoring the terms of the Geneva Convention.

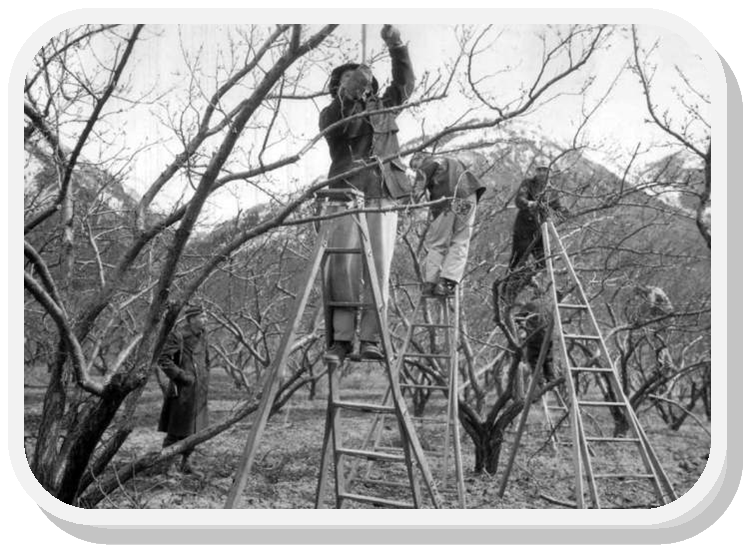

During the 1940’s, Fairfax County was an important farming and dairy producing county, the highest producing in Virginia. (By 1947, Fairfax County become the leading dairy producing county in the United States.) Food production became even more dire as the boys from the farms went to war, leaving a massive labor shortage. Convict labor was often used, but by the harvest season of 1944, less than 10% of requested labor could be offered by the prison system.

The Fairfax County Board of Supervisors then followed the example of Augusta and Rockingham Counties in the Central Shenandoah Valley, petitioning the War Department to establish a POW camp within Fairfax County; estimating that 200 prisoners would be needed to work the fields. Since labor was in high demand throughout the entire country, the local Agricultural Extension Agent had to obtain a Certificate of Need from the local office of the War Manpower Commission. Compelling documents were submitted to convince the War Dept. that every means of finding labor had been exhausted. Besides convicts, scout troops, the Women’s Land Army of America (also known as the Crop Corps), conscientious objectors, high school and college students were employed on many farms, especially during summer and holiday breaks. (4)

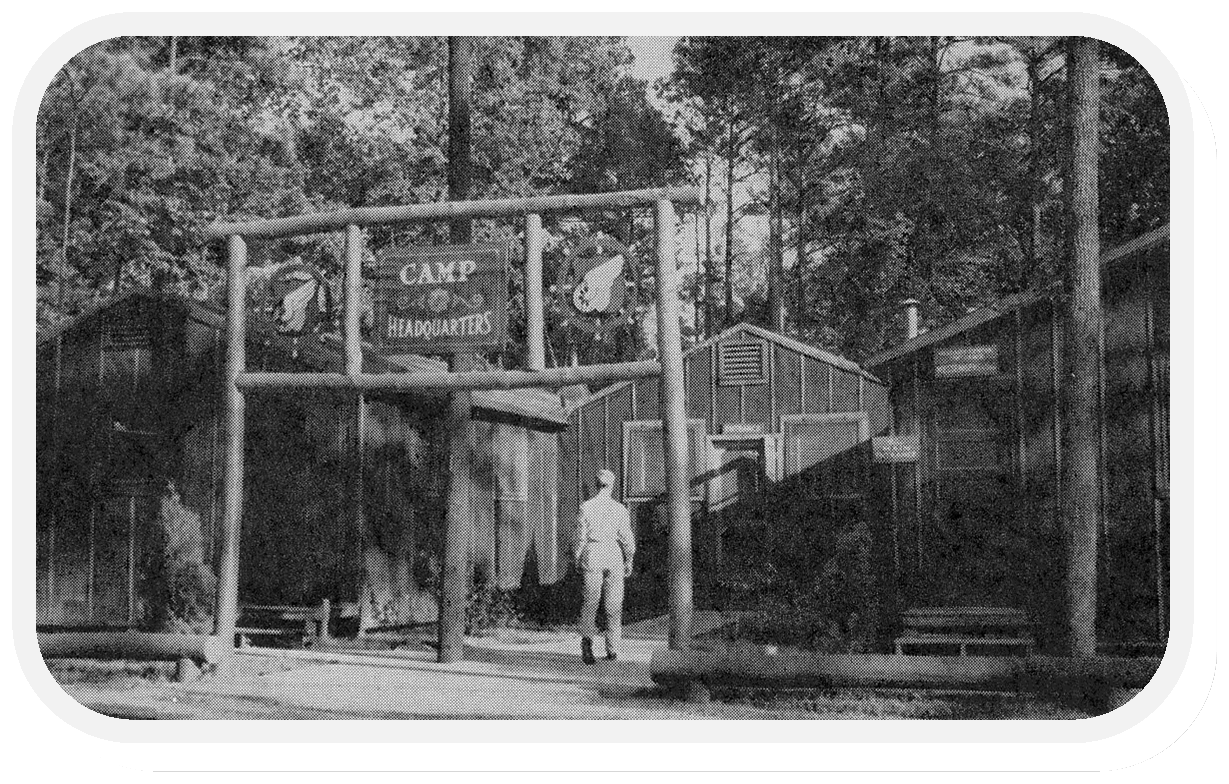

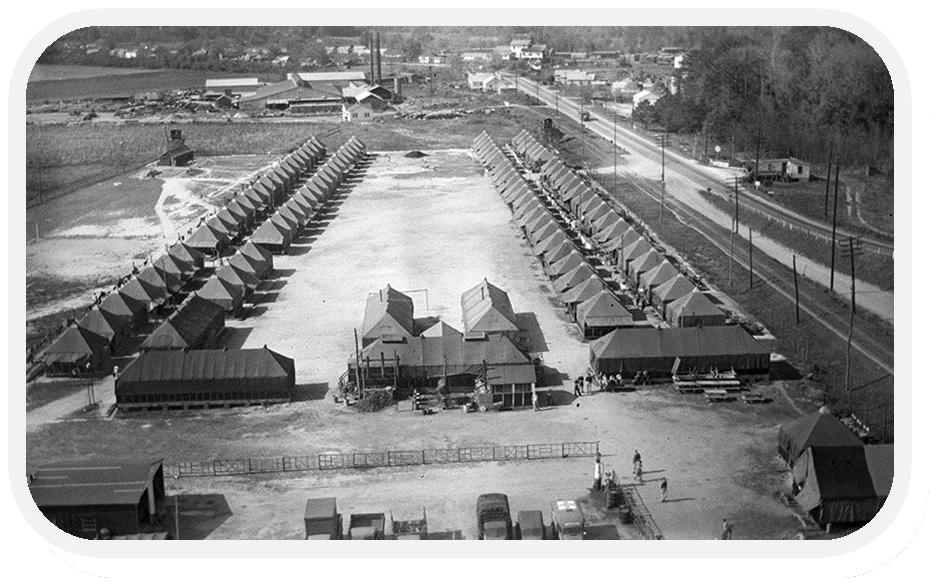

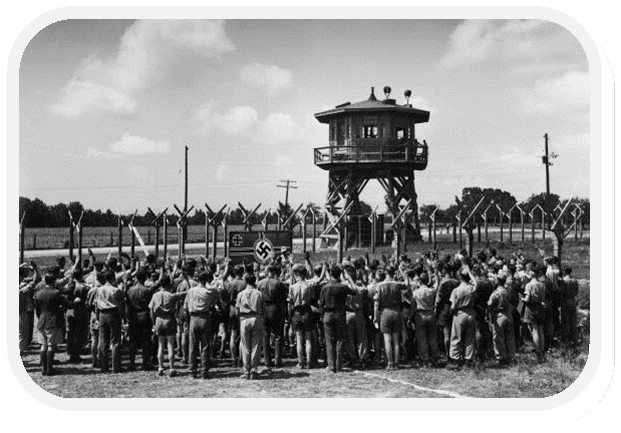

Evidentially, Fairfax County was able to prove the need, and a camp was built by June 1945 at the former State Road Convict Camp on the site now occupied by Public Storage (mini storage units) at Waples Mill (north side of Lee Highway). The camp remained open through the harvest season, closed in November 1945 sending all 150 POW’s home to Germany. The cinder block buildings remained until the mid 1970’s.

In a report submitted to the Fairfax County Agricultural Cooperative Association by state extension agent, LS Greene:

“The first prisoners arrived on June 13, 1945 and left on Nov. 16 that same year. During those five months, an average of 150 prisoners put in 111,000 hours for 198 local farmers and husked 3,500 shocks of corn. For their efforts, they received a symbolic amount of $1 a day in canteen coupons.”

The camp measured 400 ft. x 200 ft. with multiple perimeter fences topped with barbed wire, and a watch tower always manned by two guards. Initially, county residents worried about prisoner escapes; learning later that escape was unlikely since prisoners realized that this camp was not a bad place to wait out the war. It was also occupied by lower ranking soldiers. The prisoners in Fairfax, along with the rest of the POW system, were well fed, fairly treated, and offered continuing education. In fact, they were fed the same meals eaten by the guards, and paid the prevailing wage of the day. Additionally, not all prisoners spoke English, nor knew the geography which deterred escapes.

Local residents, recalled their experiences with the Germans in Margaret Peck’s book, Voices of Chantilly. Resident, Lewis Hutchison wrote:

"In the 40's there was a Prisoner of War camp at 29/211 and German POWs would come to the farms to help. Two of the POWs named Fritz and Hans [cphug184: But of course!] helped us during the summer and I was quite fond of them. Fritz drew a picture of me from my school picture, and Hans made me a ring from a quarter and a dime, both of which I still have." He continued by saying they painted another local farmer's roof and as kids they wondered if they were sending signals to the Germans.”

Margie Ann Dick, remembers that in the summer of 1945,

“Locals were notified they could use the Germans as labor. After several weeks of getting two new prisoners each day, they petitioned to keep the same two, so they would not have to re-explain the process of farming, etc. each day. That was allowed. They could not pronounce the names of the two POWs and called them Bill and Sam. They stayed with the family until November of 1945 and when they left she said it was just like family leaving. The local women were not allowed to talk to the POWs, but they did. And were not allowed to feed them, but they did. The POWs were picked up at 7:00 am and returned at 6:00 every day, but Sunday. If they were working late, the farmers needed to call the camp and notify the guards. Local farmers would pay the army...and some of which made it to the hands of the prisoners where they could buy sodas and cigarettes at the camp canteen.” (5)

Respect, if not friendship, grew between the prisoners and the farmers, based on their agricultural backgrounds, industriousness, and often shared religions.

SHORT FACTS

- 425,000 German prisoners lived in 700 camps in 46 states throughout the United States during WW II.

- After the United States entered World War II, the Government of the United Kingdom requested American help with housing prisoners of war due to extreme housing & food shortages in Britain.

- The prisoners were usually transported in Liberty Ships returning to the US, that would otherwise be empty, with as many as 30,000 arriving per month.

- Most German prisoners were pleased to be captured by the British or Americans, if captured they must be, as there was a general terror in being captured by the Russians.

- Pullman cars, which transported prisoners to their prison camps, were an early introduction to the industrial accomplishments of the US. Prisoners, who generally did not harbor long standing animosity toward Americans, found that their new enemy was a more formidable foe than German propaganda had credited.

- Less than 1% of prisoners tried to escape.

- Camps resembled the average US training sites, except for the barbed wire and watchtowers.

- The Geneva Convention required a living space of 40 sq.’ per enlisted man and 120 sq.’ per officer, which was provided.

- The Geneva Convention also mandated equal treatment for prisoners, meaning that they were paid American military wages. Work was provided in manufacturing, lumber, and agricultural industries; Officers could not be compelled to work, but many did voluntarily and were paid the same wage as enlisted personnel.

- Prisoners could not be used in work directly related to the war effort such as ammunition or tank production, or in dangerous conditions. The minimum pay for enlisted soldiers was $0.80 a day, roughly equivalent to the pay of an American private.

- While language differences and risk of escape were disadvantages, prisoner workers were readily available and in the exact numbers needed. While prisoners on average worked more slowly and produced less than civilians, their work was also more reliable and of higher quality. Part of their wages helped pay for the POW program, and the workers could use the rest as pocket money for the camp canteen.

- Prisoners were paid in scrip. All their hard currency was confiscated with other personal possessions during initial processing, but returned after the war as mandated by the Convention.

- Agriculture labor was especially in demand due to wartime labor shortages. Fortunately, many prisoners had an agricultural background, adding skill to their chores and a common bond with the farmers.

- Most prisoners developed positive feelings about the US, a reasonable command of the English language, and returned to a financially devastated Germany with several hundred dollars in earnings.

- The POW Program was run by the Army Office of the Provost Marshal General.

- Money POW’s earned during their time of internment came as a blessing, and in some cases, meant life or starvation as they returned to war ravaged Germany which was suffering from rampaging inflation.

(1) Sytko, Glenn, "German POWs in North America", Uboat.net. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

(2) Wehrmacht Autumns; German Prisoners of War in the Plains Area of Rockingham County, Virginia During World War II by Gregory L. Owen.

(3) Sytko, Glenn, "German POWs in North America", Uboat.net. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

(4) Stephenson, Megan, "How Did Americans Feel About Incarcerating German POW's in W. W. II on US Soil?", History News Network. Published by George Mason University. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

(5) Peck, Margaret, “Voices of Chantilly”, 1996.

This article was first reported in the ENDEAVOR News Magazine, October 2014 edition. No reproduction of this article, in whole or in part, is permitted without the written permission of the author. (Copyright © 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. (Photographs & images, on this page, and on this website, are not available for use by other publications, blogs, individuals, websites, or social media sites.)

(Copyright © 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. Photographs are from the Library of Congress, Imperial War Museum, Library of Virginia, Wikipedia, and private collections. (Photographs & images, on this page, and on this website, are not available for use by other publications, blogs, individuals, websites, or social media sites.)

Copyright 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy