The Death of George Washington

A Glimpse into the Past of Demaine Funeral Home

The Demaine Funeral Home finds its origin dating back to 1789 when families would turn to their local cabinetmaker to build a casket.

The Demaine Funeral Home finds its origin dating back to 1789 when families would turn to their local cabinetmaker to build a casket.

Ingle & McMunn, was such a business in early Alexandria, who had in their employ a young and promising cabinetmaker, William Demaine. It was Demaine, only in his mid-teens, who thought it foolish that families should have to wait for a coffin to be made, and used his free time to build an assortment in advance. However, when an exhausted and cold messenger banged on the shop’s door, early on Sunday morning in December with the news that Gen. George Washington, at the age of 67, had died at 10:20 pm the night before, it was truly a morning never to be forgotten.

It was December 14th, 1799, when Washington’s personal secretary, Tobias Lear sent this messenger to embark on the 14 mile ride from the Mt. Vernon estate with the General’s measurements to have a casket made.

Gen. Washington, at six feet-three and a half inches tall, was a giant of a man for his time, which eliminated considering any casket in stock. Besides, this was no ordinary citizen, and called for something befitting the Father of Our Country. A mahogany casket, lined in lead, was decided upon.

While no account of exactly who did what was ever recorded, it follows that the proprietors, Joseph and Henry Ingle would have lent their wood-working talents to such an important task, as well as call upon the experience of William Demaine who was largely responsible for coffin construction at the Ingle & McMunn firm. Washington’s request was to be buried no sooner than three days after his passing in order to allow time to notify friends and family. Both of Washington’s attending physicians, Dr. Dick, and Dr. Craig, not certain as to the cause of Washington’s death were concerned that it could be communicable, and insisted that the funeral not be delayed, due to weather or otherwise, past the fourth day. All other work in the shop was put aside, in order to tackle the demanding deadline and unprecedented request.

Washington’s body was not embalmed, but pleased in a room just off the rear porch at Mt. Vernon with the windows open, allowing the December chill to preserve his body until burial. Time was needed for Gen. Washington’s brother, Beauregard Washington, among others, to be informed and to ride from Philadelphia for the service. The Rev. Thomas David, rector of Christ Episcopal Church in Alexandria, where Washington attended, was asked to perform the religious portion of the funeral. Historical information provided by the Demaine Funeral Home, compiled by Diane Downey.

Undertaker Services

“Today we rely on the services of a funeral home director, or undertaker, for much of the burial preparation for decease loved ones. In the eighteenth century, an undertaker was in fact a contractor -- one who undertakes to provide a service. Any service. Since embalming was not yet a standard practice, nor were corpses laid out in funeral homes, an undertaker as we know him/her today did not exist at the time of Washington’s death.” (1)

According to the THE BURIAL OF GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, The Lesser Known Participants by Richard Klingenmaier: “In the eighteenth century all supporting services for a funeral were provided by various individuals hired for their specific skills. In England, where most early American burial practices originated, the burial process in the 18th century was much more clearly defined and better organized as a service industry. The participants were Undertakers, Coffin Makers, and Funeral Furnishers. They were often competitors, but also provided material support to each other. All three were distinct branches of the English funeral trade. The Undertaker, who might be his own coffin maker, generally provided funerals to the lower end of the social scale, and therefore, they were less elaborate. Whereas, the Coffin Maker made his living by making his own coffins, selling them directly or indirectly to customers, and occasionally performed funerals.

The Funeral Furnisher, on the other hand, purchased his coffins from the coffin maker, or made his own, including dressing and upholstering them himself, and provided from his special warehouse supply of soft furnishings, all the other required accessories -- special coffin hardware, "grave clothing," black crepe, family hatchments, mourning hat and arm bands, gloves, shrouds, palls, cloaks, mourning clothing, and hearse, carriages and horses. It was the Funeral Furnisher who catered to the wealthy.

In late eighteenth century Alexandria the more organized and competitive funeral trade as practiced in England had not yet been established. In the case of George Washington's funeral arrangements, the Washington estate was served by individuals who provided distinct burial preparation services, as individual undertakers or contractors.

The cost of a late eighteenth century funeral would depend on the decease's place in society as well as how much the family could afford. The most expensive part of the burial process could be the burial casket. Probably less than 1% of burials, however, included caskets constructed of expensive mahogany; most people were buried in less expensive, plain wooden caskets made of pine, walnut, poplar, or cherry, or in the case of the very poor, simply wrapped in a burial shroud and placed in the grave. Clearly the wealthy and those considered the social and/or political elite -- including George Washington -- could and were expected to afford a more elaborate burial. Cost escalated if specialized labor was employed rather than services provided by family and employees. If you had to hire a grave digger, have someone wash, dress and coifed the deceased for burial.

The Ingles billed Washington's estate $99.25; $88.00 for the casket with engraved silver plates and furnished with black lace, handles and a covered case with lifters. An additional $11.25 was charged for hiring a coach, a bier, and a horse for delivery. A coppersmith and plumber located a block away on South Fairfax Street, was probably tasked by the Ingle brothers directly to provide the lead liner, for which he was paid 14 pounds 10 shillings (roughly $59.00 in 1799 currency).

George Washington's funeral costs (those actually billed to his estate) were about 260.00 dollars in U.S. currency of 1799. That figure equates to approximately 62 British pounds at that time. The value of those 62 pounds in modern-day dollars (2010) has been calculated to be $6,386.3 Interestingly, the average cost of a m odern-day funeral is calculated to be about $7,000 according to the insurance industry.

odern-day funeral is calculated to be about $7,000 according to the insurance industry.

Following instructions in his will, Washington's military funeral took place on December 18, 1799 at Mount Vernon restricted to family, friends, and associates, rather than a grandiose state funeral. The funeral started at 3:00 PM, when a schooner moored in the Potomac began firing its guns every minute. Inscriptions on the silver-plate of Washington's coffin included Surge Ad Judicium, meaning rise to judgement, and Gloria Deo meaning glory to God.

Military officers and fellow masons served as pallbearers while a musical band from Alexandria played a funeral dirge. A masonic apron and Washington's sword adorned his coffin. Washington's body was interred inside his communal family vault at his beloved home. Mount Vernon has since become a patriotic destination for the American public to pay tribute to George Washington and for his contributions as the first President under the Constitution, and for his leadership as Commanding General during the American Revolutionary War.”

TOOLS OF THE TRADE:

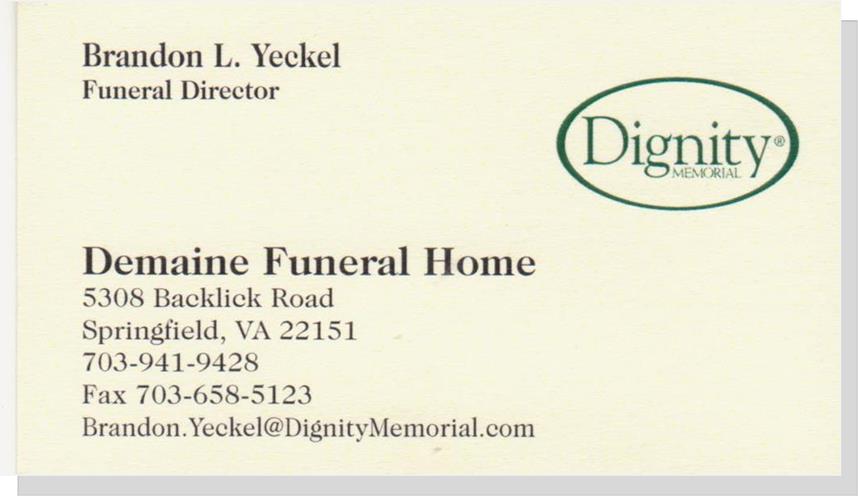

The very wood working tools, handed down from generation to generation in the Demaine family, and used by William Demaine in the shaping and molding of the first president’s casket, are displayed, from time to time, at the present Demaine Funeral home locations in Alexandria and Springfield.

(1) "THE BURIAL OF GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, The Lesser Known Participants” by Richard Klingenmaier as published by the Alexandria Historical Society, Spring 2012 and Wikipedia: Death of George Washington

Painting: Junius Brutus Stearns, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Copyright © 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. (Photographs & images, on this page, and on this website, are not available for use by other publications, blogs, individuals, websites, or social media sites.)

Copyright 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy