VIEW ON NATURE: Old-Growth Greatness

By: Stephen L. Wendt

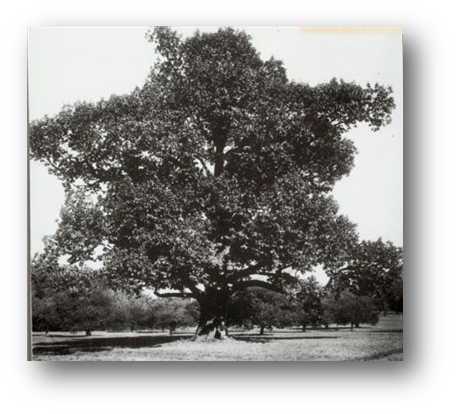

Chestnuts, Photo by Stephen L. Wendt

Many of us think of the forest when Nature comes to mind. All of our lives we lived amongst trees, be it a lone silver maple in your front yard or a tall stand of oaks in the back forty. Trees are and will remain a part of our own ecosystems.

Closer examination reveals the established woodlands we see today are second-growth forests, from 100 years or more ago. Virgin forests once covered much of the Eastern U. S. and Pacific Northwest. Sadly, only about one percent of those uncut stands remains east of the Mississippi River. What caused this? Quite simply, progressive commercial and industrial logging, and a fungal tree disease from Asia.

Settlement and expansion between the 1600s and 1700s were relatively modest. Settlors only cleared trees from a few acres to build homesteads and grow personal crops. But the growth of villages, towns and then cities fueled commercial downing of forests for timber in the 1800s. Old-growth forests that thrived for centuries, especially in the south, were replaced with softwood pine plantations.

The American chestnut dominated much of eastern U.S. among the largest, tallest, and fastest growing trees before they were slowly wiped out in the first half of the 20th century by a fungal blight, the greatest tragedy in American forest history. Back then, the forest was a dark shadowy expanse that the Lewis and Clarke expedition warily saw dissipate, once upon the Great Plains.

Uncut and less cut forests host more diverse ecosystems and biodiversity. Surveys have established finding almost 500 salamanders per acre as compared to 100 salamanders in younger woods. Many species of lichens, mushrooms, and insects are only found in old-growth timbers.

Today’s old-growth forest stands have towering 100+ foot high canopies. Giant trees of different species and numerous fallen tree trunks in different stages of decomposition back are signs of virgin forests. Another clue is the presence of huge bends or unusual growth patterns in mature tree trunks, indicators of past disruptions in natural growth often caused by other trees falling on neighboring saplings and sudden shifts in nutrient light availability. Naturalists call this ability for trees to adapt by curving growth “sinuosity”.

Another rapidly scientific interest re: trees, especially in old-growth areas, is the growing evidence that trees are connected by vast networks of fungal networks in and amongst tree roots. This has opened a wide series of studies about the subterranean interaction, likely chemical communications amongst trees as a community.

An amazing old-growth stands grows on the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg known as Stadium Woods. This rare forest consists of 11.5 acres of large to very large trees, including dozens of white oaks over 300 years old. The university considered clearing this miracle forest until significant public outcry and VA Tech’s realization of its truly unique historic, educational, and research importance.

I will never forget walking through Stadium Woods with its absolutely giant, towering white oaks with massive thick trunks which significantly spread into a higher layer of huge 3+ ft diameter branching beginning at the height of 75 feet up! That’s where old-growth greatness beacons.

During the early to mid 20th century, American chestnut trees were devastated by chestnut blight, a fungal disease that came from Chinese chestnut trees that were introduced into North America from East Asia. It is estimated that the blight killed between 3 and 4 billion American chestnut trees in the first half of the 20th century, beginning in 1904. Very few mature specimens of the tree exist within its historical range, although many small shoots of the former live trees remain.

The blight was first found in the chestnut trees on the grounds of The New York Zoological Garden (Bronx Zoo) by Herman W. Merkel, a forester at the zoo. In 1905, Murrill isolated and described the fungus responsible (which he named Diaporthe parasitica), and demonstrated by inoculation into healthy plants that the fungus caused the disease. By 1940, most mature American chestnut trees had been wiped out by the disease.

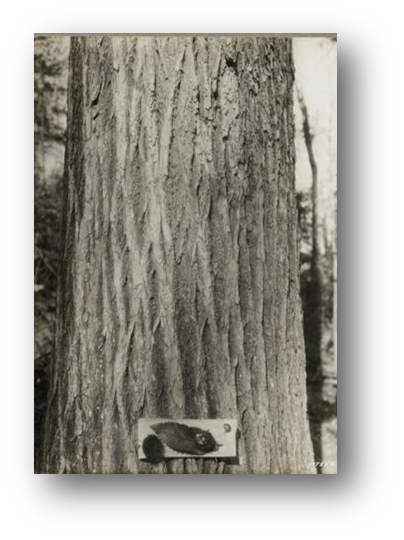

The reddish-brown wood of the American chestnut was lightweight, soft, easy to split, very resistant to decay, and did not warp or shrink. For three centuries many barns and homes near the Appalachian Mountains were made from American chestnut. Its straight-grained wood was ideal for building furniture and caskets. The fruit that fell to the ground was an important cash crop and food source. The bark and wood were rich in tannic acid, which provided tannins for use in the tanning of leather. Many native animals fed on chestnuts, and chestnuts were used for livestock feed, which kept the cost of raising livestock low.

Efforts started in the 1930s and are still ongoing, to repopulate the country with chestnut trees. Wikipedia

Reproduction of any article or photograph requires the written permission of the

The ENDEAVOR News Magazine. Unless otherwise noted, photographs are courtesy of the Annandale Chamber of Commerce photographic archive, Wikipedia, and private collections with all rights reserved.

(Copyright © 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. (Photographs & images, on this page, and on this website, are not available for use by other publications, blogs, individuals, websites, or social media sites.)

Chestnut tree in Howard Co, MD

Chestnut tree in Howard Co, MD

Courtesy of National Archives

Late spring foliage of the American chestnut, Castanea dentata. Tree located in West State Street Park, Athens, Ohio.||Creative Commons: Jaknouse ,

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

From tree identification file courtesy of National Archives, Chestnut tree with rugged bark, used as a favorite building material in Appalachia Mountains between mid 1600s and late 1800s.

Photo credit: Stephen L. Wendt with all rights reserved.

(Copyright © 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. (Photographs & images, on this page, and on this website, are not available for use by other publications, blogs, individuals, websites, or social media sites.)

Copyright 2012 Annandale Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy